What is Project Control ?

The term control has several meanings. Those new to project management are initially dismayed by the use of the term "control", because they mistakenly equate it with the concept of authority. In the world of project management, control has very little to do with telling people what to do, dictating their actions or thoughts or trying force them to behave in certain way - all of which are common interpretations of control. In project management, the term "control" much more analogous to steering a ship. It's about continually making course adjustments with one main objective in mind-- bringing the ship into safe harbor, as promised at the start of the voyage. And the successful project voyage includes identifying a specific destination, carefully charting a course to get there, evaluating location throughout the voyage and keeping a watchful eye on what lies ahead.

Project controls are tools developed to diagnose the system for deviations from the actual plan and reset them back with the actual plans/schedule. Project controls are required to check whether the project is progressing in accordance with the plans and standards set during the planning phase. In fact, project controls are measures taken by the project manager in order to minimize the gap between the planned output and the delivered output.

Objectives of Project Control

Following are the objectives of project control :

1) Primary Objective :

The primary objective of control is regulation. The purpose is to monitor the delivered output by comparing it with the actual/scheduled output suggested in the planning phase. The regulatory function of control helps in :

- Translating the objectives into performance standards that are represented by program activities and events.

- Formulating budgets in order to compare the delivered output with the actual/scheduled output.

2) Secondary Objective :

The secondary objective of control is conservation of resources. The project manager is entrusted the responsibility of protecting the physical, human and financial resources of the organization.

- Physical asset control is the process of controlling the use of physical assets. It includes the preventive or corrective maintenance of the assets. A project manager has to schedule the maintenance/ replacement plan in a way as to minimize interruption to the work in progress and without overlooking the quality aspect.

- Human resource control is the process of controlling and maintaining the growth and development of the human capital of the organization. Conserving human resource is therefore a significant aspect of the control system.

- Financial resource control is a combination of regulatory and conservatory functions. The regulatory and conservatory techniques of financial resource control consist of a control on current assets and project budgets along with capital investments.

3) Tertiary Objective :

The tertiary objective of project control is to facilitate decision-making. Effective decision-making by the management requires the following reports :

- A report comprising the plan, schedule and budget made during the planning phase.

- Data consisting of the comparison between the resources spent in order to achieve the delivered output and the scheduled output. This report should also include an estimation of the remaining work.

- An estimate of the resources required for the completion of the project.

Features of Project Control

In project control, the emphasis is on scope, quality, schedule and cost.

1) Scope Change Control :

A change in project scope is an alteration to the original, agreed-upon scope statement defined in the project plan and specified in the WBS. Projects have a natural tendency to grow over time because of changes and additions in the scope, a phenomenon called "creeping scope". Changes or additions to the scope reflect changes in requirements and work definition that usually result in time and cost increases. The aim of scope change control is to identify where changes have occurred, ensure the changes are necessary and/or beneficial, contain or delimit the changes wherever possible and manage the implementation of changes. Because changes in scope directly impact schedules and costs, controlling scope changes is an important aspect of controlling schedules and costs. Scope change control is implemented through the change control system and configuration management.

2) Quality Control :

Quality is synonymous with ability to conform to the requirements of the end-item and work processes and procedures. Quality control is managing the work to achieve the desired requirements and specifications, taking preventive measures to keep errors and mistakes out of the work process and determining and eliminating the sources of errors and mistakes as they occur. The quality plan describes necessary "quality conditions" for every work package, i.e., prerequisites or stipulations about what must exist before, during and after the work package to ensure quality. The quality plan should specify the measures and procedures (tests, inspections, reviews, etc.) to assess conditions and progress toward meeting requirements.

3) Schedule Control :

The intent of schedule control is to keep the project on schedule and minimize schedule overruns. One cause of project schedule overruns is poor planning and, especially, poor definition and time estimating. However, even when projects are carefully planned and estimated, they can fall behind schedule from causes beyond anyone's control, including, e.g., changes in project scope, weather problems and interrupted shipments of materials.

4) Cost Control :

Cost control tracks expenditures versus budgets to detect variances. It seeks to eliminate unauthorized or inappropriate expenditures and to minimize or contain cost changes. It identifies why variances occur, where changes to cost baselines are necessary and what cost changes are reflected in budgets and cost baselines. Cost control is accomplished at both the work-package level and the project level using the cost account structure and PCAS.

Types of Project Control

There are three types of basic project control :

1) Cybernetic Control :

Cybernetic controls, also known as steering controls, are very common control systems. Automatic operation is its chief characteristic. A cybernetic control is like a steering in an automobile that enables the controller to keep the project on track. Cybernetic controls are generally used to monitor and control tasks that are carried out more or less continuously, e.g., software projects. The designing of cybernetic controls requires identifying mechanical tasks, based on the Work Breakdown Structure. A cybernetic control system that minimizes the variation from the set standards is known as a negative feedback loop. The control mechanism in a cybernetic control system acts in a direction that is opposite to the one in which the variation moves away from the standard. Also the speed of action of a control is directly proportionate to the size of variation from the standard.

2) Go/No-go Controls :

As cost and time over-runs may require the organization to pay penalties to the customer, Go/No-go controls are instituted to check whether the output meets the preset cost and time standards. These control systems are flexible and apply to all the aspects of project management. The project plan, budget and schedule are the control documents that contain preset milestones that act as verification points. Controls are usually done at the level of detail in the project plan, budget and schedule. The periodicities with which Go/no-go controls are operated are regular and preset. Preset intervals are decided upon with the help of calendars or the operating cycles. The major difference between the cybernetic and the Go/No-go control system is that a cybernetic system functions automatically and continuously, while a go/no-go system functions only when it is put into application by the controller and is periodic.

3) Post Controls :

These are the control systems that are applied after the completion of the project. These are also called post project controls or reviews. According to George Santayana, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it". Thus, while cybernetic and Go/No-go controls help a firm to accomplish the goals of current projects, post control tries to enhance the firm's chances of meeting future project goals, on the basis of lessons learnt in the past projects.

Internal and External Project Control

Both internal and external control systems are used to monitor and regulate project activities, Internal control refers to the contractor's systems and procedures for monitoring work and taking corrective action. External control refers to the additional procedures and standards imposed by the client, including taking over project co-ordination and administration functions. Military and government contracts, e.g., impose external control by stipulating the following of the contractor:

- Frequent reports on overall project performance.

- Reports on schedules, cost and technical performance.

- Inspections of work by government program managers.

- Inspection of books and records of the contractor.

- Strict terms on allowable project costs, pricing policies and so on.

External controls can be a source of annoyance and aggravation to the contractor because, superimposed on internal controls, they create management turmoil and increase the cost of the project. Nonetheless, they are sometimes necessary to protect the interests of the client. To help minimize conflicts and keep costs down. contractors and clients should work together to establish agreed-upon plans, compatible specifications and joint methods for monitoring work.

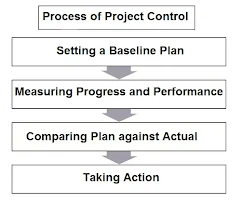

Process of Project Control

Control is the process of comparing actual performance against plan to identify deviations, evaluate possible alternative courses of actions and take appropriate corrective action. The project control steps for measuring and evaluating project performance are explained below :

1) Setting a Baseline Plan :

The baseline plan provides us with the elements for measuring performance. The baseline process, while a key to project control, is often misunderstood. A baseline is defined as the original plan for a project, a work package, or an activity, plus or minus approved changes. A modifier (Project Budget Estimate schedule baseline, performance measurement baseline) is usually included. A baseline provides the "ruler" that a project can be evaluated with. If the schedule baseline plan indicates that you should be 30 percent finished with a specific activity at a specific point, and you are 15 percent finished or 90 percent finished, you have a variance, however, further investigation is needed before an opinion can be formed about the significance of the variance.

Baseline changes are significant events and should not be made without consideration of their impact. Baseline changes are only made to reflect a change in project scope, not just to reflect when the project is behind schedule. A baseline change adjusts the ruler for the project. A variance does not justify a baseline change. It only indicates that the initial plan was not accurate. Baseline change should be facilitated through a normal change control process.

2) Measuring Progress and Performance :

Progress and performance measurement is the process of measuring the expenditure or status of non-monetary resources on a project (e.g., tracking the receipt of materials or consumption of labor hours) and the degree of completion or status of project work packages or deliverables (e.g., the extent that materials have been installed, deliverables completed, or milestones achieved), as well as observations of how work is being performed (e.g., work sampling). Together with project cost accounting measures of the commitment and expenditure of money progress and performance measures are the basis for project performance assessment.

The progress and performance measurement process includes a variety of work, resource, and process performance measurement steps. The process is integrated with project cost accounting measurement. Time and budgets are quantitative measures of performance that readily fit into the integrated information system. Qualitative measures such as meeting customer technical specifications and product function are most frequently determined by on-site inspection or actual use. Measurement of time performance is relatively easy and obvious. That is, the critical path early, on schedule or late; is the slack of near-critical paths decreasing to cause new critical activities? Measuring performance against budget (e.g., money, units in place, labor hours) is more difficult and is not simply a case of comparing actual versus budget. Earned Value is necessary to provide a realistic estimate of performance against a time-phased budget. Earned Value will be defined as the budgeted cost of the work performed (EV).

3) Comparing Plan against Actual :

Project performance assessment is the process of comparing actual project performance against planned performance and identifying variances from planned performance. It also includes general methods of identifying opportunities for performance improvement and risk factors to be addressed. Because plans seldom materialize as expected, it becomes imperative to measure deviations from plan to determine if action is necessary.

After the variances, opportunities, and risks are identified, actions to address them, and the potential effects of the actions on project outcomes, are further assessed and managed through the forecasting and change management processes. Corrective or change actions are then implemented as appropriate through updated project control planning, which closes the project control cycle. At project closeout, the final assessments of project performance are captured in the project historical database for use in future project scope development and planning.

Performance against each aspect of the project plan must be assessed. Project cost accounting measures of the commitment and expenditure of money are compared to the cost plan or budget. Resource tracking measures (e.g., the receipt of materials or consumption of labour hours) are compared to the resource plans. Schedule status (as reflected in the statues network schedule) is compared to the baseline or target schedule. Also, the project status is assessed to determine if any risk factors, identified in the risk management plan or otherwise, are imminent occurring.

During the early planning phases of a project life cycle, work performance is assessed against the project control plan established specifically for that phase and for which partial funds and resources have been authorized. At the same time, the effects of scope development on the overall capital budget and schedule targets for the project are assessed. In other words, day-to-day performance of planning activities is assessed against the project control budget for that phase, while the scope being planned is assessed against the capital budget.

The level of understanding of project performance is increased when the assessment integrates the evaluation of each aspect of the project plan. One method of integrating schedule and budget assessment is called earned value management. Periodic monitoring and measuring the status of the project allow for comparisons of actual versus expected plans. It is crucial that the timing of status reports be frequent enough to allow for early detection of variations from plan and early correction of causes. Usually status reports should take place every one to four weeks to be useful and allow for proactive correction.

4) Taking Action :

Taking corrective action first requires identifying the problem, and then implementing a potential solution. If deviations from plans are significant, corrective action will be needed to bring the project back in line with the original or revised plan. In some cases, conditions or scope can change, which, in turn, will require a change in the baseline plan to recognize new information.

Accounting System for Project Control

Cost accounting system uses following elements for project control :

1) PERT/Cost Systems :

It has been realized that traditional cost variance analysis alone is insufficient; information also s needed on work progress. Early attempts to correct for this using PERT/CPM went to the opposite extreme by ignoring costs and focusing entirely on work progress. If PERT/CPM users wanted to integrate cost control with network planning methods they had to develop their own systems.

A PERT-based system which combined cost-accounting with scheduling called PERT/Cost. The system became mandatory for all military and R&D contracts with the Department of Defense and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (DOD/NASA), Any contractor wanting to bid to DOD/NASA had to demonstrate the ability to use the system and to produce the necessary reports. Although this mandate increased usage of PERT/Cost, it also created resentment. Many firms found the project-oriented PERT/Cost system an expensive duplication of or incompatible with, existing functionally oriented accounting systems. Interestingly, many firms not involved in DOD/NASA bidding voluntarily adopted PERT/Cost with far fewer complaints.

PERT/Cost was a major improvement over traditional cost-accounting techniques because it blended costs with work schedules. Just as important, it spurred the development of other more sophisticated systems to track and report work progress and costs on a project rather than a fiscal/functional basis, PERT/Cost was the original network-based PCAS. Hereafter the term PCAS will be used to refer to any network-based cost-accounting system that incorporates PERT/Cost principles.

Most PCASs integrate work packages, cost accounts and project schedules into a unified project control package. They permit cost and scheduling overruns to be identified and causes to be quickly pinpointed among numerous work packages or cost accounts. Rapid identification and correction of problems are the greatest advantages of modern PCASs. Two elements common to most of these systems are use of work packages and cost accounts as basic data collection units and the concept of earned value to measure project performance.

2) Earned Value Concept :

Costs are budgeted period-by-period for each work package or cost account (time-phased budgeting). Once the project begins, work progress and actual costs are tracked every period and compared to these budgeted costs. Managers measure and track work progress using the concept of earned value. Roughly, earned value represents an estimate of the "percentage of work completed".

3) Work Package and Cost Account Control :

Each work package is considered a contract for a specific job, with a manager or supervisor responsible for overseeing costs and work performance. A cost account consists of one or more work packages. Both include information such as work descriptions, time-phased budgets, work plans and schedules, people responsible, resource requirements and so on. During the project, work packages and cost accounts are the focal point for data collection, work progress evaluation, problem assessment and corrective action.

Early PERT/Cost systems were inadequate for two reasons. First was the problem of how to handle overhead expenses. Typically, work packages are identified in either of two ways :

- As end products when they result in a physical product and have scheduled start and finish dates.

- As level of effort when they have no physical end product and are "ongoing" such as testing or maintenance. Given that there is usually no direct connection between company overhead and either of these kinds of work packages, there is a problem with arbitrarily allocating overhead expenses to them. Any arbitrary allocation of expenses reduces expense control and distorts the apparent performance of work packages. Work package managers have little influence on overhead, yet such costs are a frequent source of overruns.

In current PCASs the problem is resolved in two ways. First, any expenses such as supervisory and management overhead that can be traced to specific work packages are allocated directly to them. Second, any overhead that cannot be traced to specific work packages is separated by using either an "overhead" work package for the entire project (lasting for the duration of the project) or a series of shorter duration overhead work packages. Overhead work packages are kept "open" for the duration of the project and extended as needed if the project is delayed.

Issues in Project Control

The various issues in project control are as follows :

1) Baseline Changes :

Changes during the life cycle of projects are inevitable and will occur. Some changes can be very beneficial to project outcomes; changes having a negative impact are the ones which everyone wishes to avoid. Careful project definition can minimize the need for changes. The price for poor project definition can be changes that result in cost over-runs, late schedules, low morale and loss of control. Change comes from external sources or from within. Externally, e.g., the customer may request changes that were not included in the original scope statement and that will require significant changes to the project and thus to the baseline. Or the government may render requirements that were not a part of the original plan and that require a revision of the project scope. Internally, stakeholders may identify unforeseen problems or improvements that change the scope of the project. In rare cases scope changes can come from several sources.

Generally, project managers monitor scope changes very carefully. They should allow scope changes only if it is clear that the project will fail without the change, the project will be improved significantly with the change or the customer wants it and will pay for it. This statement is an exaggeration, but it sets the tone for approaching baseline changes. The effect of the change on the scope and baseline should be accepted and signed-off by the project customer. Care should be taken to not use baseline changes to disguise poor performance on past or current work.

2) Contingency Reserve :

Plans seldom materialize in every detail as estimated - identified and unidentified risks occur, estimates are wrong, the customer wants changes, technology changes. Because perfect planning doesn't exist, some contingency funds should be agreed upon before the project commences to cover the unexpected. The size of the contingency reserve should be related to the uncertainty and risk of schedule and cost estimate inaccuracies. Contingency reserve is not a free lunch for all who come. Reserve funds should only be released by the project manager on a very formal and documented basis. The trend today is to allow all stakeholders to know the size of the contingency reserve (even sub-contractors). This approach is built on trust, openness and the self-discipline of the project stakeholders who are all focused on one set of goals.

3) Scope Creep :

Large changes in scope are easily identified. It is the "minor refinements" that eventually build to be major scope changes that can cause problems. These small refinements are known in the field as scope creep. For example, the customer of a software developer requested small changes in the development of a custom accounting software package. After several minor refinements, it became apparent the changes represented a significant enlargement of the original project scope. The result was an unhappy customer and a development firm that lost money and reputation.

Scope creep is common early in projects- especially in new-product development projects. Customer requirements for additional features, new technology, poor design assumptions, etc., all manifests pressures for scope changes. Frequently these changes are small and go unnoticed until time delays or cost over-runs are observed. Scope creep affects the organization, project team and project suppliers. Scope changes alter the organization's cash flow requirements in the form of fewer or additional resources, which may also affect other projects. Frequent changes eventually wear down team motivation and cohesiveness. Clear teams goals are altered become less focused and cease being the focal point for team action. Starting over again is annoying and demoralizing to the project team because it disrupts project rhythm and lowers productivity. Project suppliers resent frequent changes because they represent higher costs and have the same effect on their team as on the project team.

Approaches to Project Control

There are two approaches of project control :

1) Variance Limits/Analysis :

One method of control analysis - once the only common method is variance analysis. This remains an important tool and relies on simple subtraction to evaluate the difference (variance) between a planned result and an actual measurement. Variance analysis can be used to show differences between planned and actual progress, or between budgeted costs and actual costs. In other branches of management, deviations from plan are also called 'exceptions' and 'management by exception' is the process of maximizing management effectiveness by concentrating on things that need attention rather than wasting time on things that do not. The following are common sources of variances (or exceptions) in the context of projects :

- Scheduled start versus actual start,

- Scheduled finish versus actual finish,

- Scheduled time for an activity versus actual time,

- Scheduled achievement time for a milestone event versus the actual achievement time,

- Budgeted cost versus actual cost,

- Measured value versus actual cost,

- Budgeted man-hours versus actual man-hours,

- Budgeted unit cost versus actual unit cost,

- Budgeted percentage complete against actual percentage complete.

Although still used extensively, variance analysis can, however, be inadequate or even misleading. It can be a meaningless guide to progress and performance. Yet, although this tells that expenditure is over budget. It does not tell that :

- Whether the project is on, above or below the expected cost performance,

- What the probable final cost of the project will be,

- Whether work is on, behind or ahead of schedule,

- What the probable project completion date will be.

To answer these questions, a subjective assessment of the 'percentage complete' can be made for comparison against these cost figures. Almost inevitably this will be optimistic and influenced by the actual figures. Subjective estimates are usually unreliable, to say the least. Thus variance analysis, used alone and not supplemented by a more reliable assessment method, suffers from the following deficiencies :

- It is purely historic and not sufficiently predictive.

- It does not indicate performance clearly and simply.

- It is insufficiently sensitive to identify problems early.

- It does not effectively use all the data available.

- When used with percentage complete assessments it tends to be highly subjective and unreliable.

- It does not indicate trends.

- It does not integrate schedule and cost. Thus, it confuses the effects of cost and schedule variances and their interactions.

In sum, variance analysis, when used on its own, is an ineffective way of analyzing and reporting project progress and performance.

2) Performance Analysis :

Project progress and performance analysis based on 'earned value' concepts. Integrate cost and schedule on a structured and personalized basis. With earned value analysis there are three elements or data required to analyze performance, which are :

- The budgeted cost scheduled up to the time of measurement,

- The actual cost at the time of measurement,

- The corresponding earned value.

The earned value is simply the budgeted value (cost or man-hours) of the work actually completed. If a job was budgeted to cost 5,00,000, when that job is completely finished its earned value is 5,00,000, even if the actual cost to complete the work happened to be 4,00,000 or 9,00,000. Subjectivity problems are minimized in the structured earned value approach, where the work is broken down into WBS elements, cost accounts and work packages. The total earned value of the work completed at the time of measurement is then based on the budgeted value of all these completed segments of work, plus an estimate to allow for active work in progress.

The following three measures can be used to determine if a project is running on schedule and within budget :

1) Actual Cost of Work Performed (ACWP) :

It is the actual cost expended to perform the work accomplished in a given period of time.

2) Budgeted Cost of Work Performed (BCWP) :

It is the budgeted cost of the work completed in a given period of time.

3) Budgeted Cost of Work Scheduled (BCWS) :

It is the budgeted cost of the work scheduled to be accomplished in a given period of time (if a baseline schedule were followed).